| Across the AtlasI

have traveled to the high valleys and picturesque villages -- Tagadirt, Azib Tifni, Imlil

-- around Marrakech in the past few days. Words will contract what images can expand; only

pictures can do justice to the High Atlas scenery. In any case, it is time to move on; my

appointment with the Army convoy faraway in Dakhla is ticking closer every second.

I get up at four; the late-October pre-dawn Marrakech is bitterly

cold. There is still no water; this serves as excuse to postpone a shower, though I would

come to have ablutionary hallucinations once in the desert.

The P31 leads south-east towards Ouarzazate. The night is still

dark, and there is fog on the road as the 4x4, lights blazing, swings onto the road that

leads up the Atlas slopes. I hope to be over the high passes in a day or so.

After two hours of monotonous driving, the daylight breaks and a

light grey green dawn washes over the road. The road passes over culverts that let through

boiling mountain streams. I pass the Rocade canal, then the angry Oued Zat . The first

stop is at a tavern named Le Coq Hardi, for a breakfast of mint tea, eggs, and toast.

This is a lonely road to the desert south, traffic doesn’t

pick up very much as the morning advances. Terraced fields lie in a green chequerboard far

below as the road climbs higher and higher. Undulating expanses of the lower hills lie all

around, far below, and my chariot climbs the highway, the upper reaches obscured by fog.

There are scattered copses of oak trees, but the hillsides are largely barren, covered

with loose-looking boulders or thorny maqui. Here and there, I see rust-colored,

ochre and verdigris stains in the washes of gullies and faces of rock – evidence of

the mineral wealth under the surface. Every hour or so, I stop lest the engine heat, and

look back over the intestinal coils of road bunched below.

The sun

climbs. I have seen a couple of villages far away in the glistening valleys, and a man or

two coaxing a recalcitrant donkey up the slopes, but the landscape has been pretty empty

of people; so I’m surprised and a little rattled when, on coming around a bend, I

come upon a man in the middle of the road, waving vigorously towards what appears to be a

ramshackle shop perched precariously halfway up the hillside. I swerve, pull over after

the road straightens out, and walk back down the slope. His weather-beaten face under a

faded cap breaks out into a gap-toothed grin as he watches me approach.

His name is Idriss. This little wooden shop in the middle of

nowhere is his livelihood. He sells tea and snacks, cigarettes, plastic-bags of walnuts

and dates, assorted pottery brilliantly colored with minerals dug up from fissures in the

rock. Woven mats and rugs hang draped over the walls. He lives, he says, 40 kms away, and

cycles up every day, rain or shine – he proudly knocks on his chest to show me how

strong his lungs are. This is a good spot, almost the halfway mark on the long stretch

between Ait Barkka and Taddert, the CTM buses usually stop for a bathroom or namaaz break

– he waves towards the direction of a cave up the hill – I see mats spread on

the floor.

He coaxes me to buy a small glazed bowl and a knife sheathed in

stone. Wrapping these up in newspaper, Idriss offers me tea to stay and talk a while; a

parked vehicle will likely draw others.

Idriss traveled to Spain when he was a teenager, and worked there

for a few years in a motel before being sent back to Morocco; he missed his mountains on

the Costa Brava beaches, and has never tried to go back. Strangely enough, on this

hillside in the High Atlas, he shows a comprehension of the wider world that I have not

encountered amongst those in Marrakech or Casa I’ve had the chance to talk to.

"How many people in Hind?" he asks. "Nine hundred

million" I reply, not remembering what’s French for a billion. Idriss is shocked

and nearly falls off his seat. "Nine – hundred – million?" he tries to

understand the number. "How many people do you think in Casa?" he asks.

"One million, perhaps two" I say. He sits for a while trying to imagine hundreds

of Casablancas and then gives up, shaking his head, a smile of wonder and envy on his

face. "Fort?" he asks, "All strong?" It is my turn to be taken

aback. I would like to say Indians are strong, but I’m not sure what measure of

strength Idriss will relate to. "Well, Hind is strong in certain ways. We have

nuclear bombs now ..." I say lamely. "You don’t say! And planes? How many

planes?" "Thousands." We talk a little more of military matters.

"Yes," Idriss says "you need to be clever to be strong. That’s what I

think. How many Mussalmans in Hind?"

What does Idriss think of Islamic government? King Hassan is the

latest in a long line of Fatimid Alawites who claim direct descent from the Prophet

through his daughter Fatima; the Sultan takes the title Amir ul-Momineen

--Commander of the Faithful. The significance of this should not be underestimated -- the

enormous prestige that a claim of descent from Muhammad lends may explain why the Fatimid

Alawites have survived while, in recent times, so many other Muslim dynasties have bitten

the dust. There is a strong anti-monarchist Islamic opposition in Morocco and the Istiqlal

(Independence) party advocates curtailing the absolute power of the Sultan, yet the baraka

of Hassan coupled with the relative disinterest the Atlas Berbers have shown in political

Islam seems to have prevented the wholesale polarization you see in, say, neighboring

Algeria.

Idriss chooses his words carefully, stirring the blackened kettle

of mint tea balanced on three slabs of ash-covered rock. "See, the ‘Ulema are

becoming powerful. The people who choose careers in the ‘Ulema come from poor

families who have no other choice. Rich men’s children from Rabat or Casa or Tangier

become les professioniels, they become medecins, ingénieurs, avocats. They

can afford to do so, and then they go to Europe or they have their own companies in the

cities. However, the parents from poorer classes want to send their children to religious medersas

as not only education in those institutions is free but students also get free boarding

and lodging.

These children grow up with a backward outlook not knowing much

about how things work outside the mosque and the medersa, or about other things in the

world. When these children become ‘Ulema, religion becomes a power in their hands

with which they rule millions of backward, poor and illiterate people. As the number of

poor people is increasing faster than the number of rich people, so the ‘Ulema are

becoming powerful faster than the teachers and lawyers. In many cases, believing educated

people who do not wish to study religion by themselves choose to follow the Ulema. This is

the problem, which causes all sorts of trouble ..."

I would like to ask him more about political Islam, but he

changes the subject and begins to talk about his children. The eldest son is eighteen, and

has just finished high school in Taddert. Idriss hopes the boy will get a government job

in the revenue collector’s office there. He has some connections due to his

wife’s family, and thinks it can be done.

It is well past noon, and I get up reluctantly. Idriss reaches

into his basket and gives me a large bag of walnuts. "Ma’a al-salaama, be

careful with the Sharqi in the Janoob."

At Taddert, I watch the tagine I’ve ordered for my late lunch cook

very slowly over hot coals. The distinctive conical ‘tagine’ pot is first lined

with prunes and apricot slices. Then carrots, beets, onions and potatoes are thrown in as

a bed, over which some meat – in this case, rabbit – is placed; it all cooks

into a sweetish stew. It is already 2 pm, and I’m nowhere near the Tichka summit that

has to be crossed. I do not want to be caught out in the high passes after sunset; but

there’s no hurrying a tagine.

As I leave Taddert, the sun is beginning to go down, and the

twists and turns in the road cause it to dazzle my eyes one minute, and obliterate my

rear-view the next. The Tizi’n’Tichka pass ahead (2260 m) is visible in the

distance as the summit over which the road disappears. It proves to be slow going as the

laden vehicle groans up the steep loops and switchbacks. On those stretches where shadows

have already fallen, it is chill and blustery. I can see the traces of snow clinging to

some of the peaks above. At 6pm, still 20 kms short of Tichka pass, darkness falls

rapidly. The road has large potholes and long sections where neither guard rail nor

shoulder is visible. Just before a sinister bend, a narrow track branches off and leads up

the hill. The Arabic inscription reads ‘Telouet Mukhaym’, followed by the

international icon for a campsite. I gratefully reverse into the steep track and park just

out of sight of the highway, taking care to turn the wheels at an angle to the track and

wedge stones under the tires for good measure. Rocks contract in the cold, destabilizing

loose boulder covered slopes such as this, and I have no desire to hear my hitherto trusty

steed bolt during the night.

I have with me a multipurpose can of propane that can be used to

cook a saucepan of Maggi and, with a filament slipped over it, can throw off enough light

to read under. I am plodding through various philosophies of Islam that originated in the

Maghreb. Ibn Rushd (Averroes) was born in 1126 in Cordoba, and spent his life shuttling

between the courts of Cordoba and Marrakech. Though he was often decried as a heretic by

both Christians and Muslims, the works of Islam's most famous platonic philosopher and

jurist grew influential in Europe, and fuelled the Reformation and Renaissance centuries

later. His own civilization, locked into a state of denial of aql and ijtihad

(reason and interpretation), remained frozen in medievalist tribalisms, and today has

little memory of him: ibn Rushd’s writings exist only in Hebrew and Latin

translation, the Arabic ones were lost centuries ago.

The Khorasani Imam al-Ghazali had said: reason leads to

skepticism, the mind is not enough to understand God. What is good? What is bad? What is

beautiful, what ugly? The mind or reason can not determine for itself. Divinely inspired

norms are needed to understand the world. Theology, which tries to bring a rational,

systematic presentation of what is unknowable, is inferior to the mystical experience of

surrendering to the infinite.

Ibn Rushd was a devout Muslim and, as such, believed in a

transcendental God separate from His creation. But he was also a philosopher, and he

wanted to bring about a complete unity. He utilized the idea of the Universal Mind. God is

the Universal Mind, and Man is an imitation, an echo of that mind. The Universal Mind is

reflected in lesser and lesser minds. Man can either save or damn himself, according to

his own action, using his own reason, which is a part of the Universal Mind, God’s

gift to him. The emphasis on reason colored ibn Rushd’s attitude to society. In his

commentaries on Greek philosophy, he laments the position of women in Islam and incisively

compares their status in Arabia to the civic equality described in Plato's Republic. His

ideas were transferred to western civilization and, combined with those of other monistic

synthesizers, became the basis for rationalism, materialism and progress. In the twilight

of a century during which the forces of materialism and progress have killed a hundred

million people, extinguished thousands of species and perhaps irrevocably altered the

planet’s climate, one feels a certain empathy for the great Sufi mystic al-Ghazali,

who would not trust the reason of man.

This is my first night in some time without a proper bed. It is miserably

cold; by four a.m., I am sore in limb and throat, and have to light the stove to keep

warm. I settle down to wait for daybreak, sitting upright against a tire, wearing my

warmest clothes and covered in a blanket, cupping a steaming mug. I have a pocket radio,

but there’s really nothing on the air, and I’m reduced to fiddling with the

short-wave tuner, listening to the chirrups and whistles, the gurgles and coos of the

cosmos ebb and flow across the ether.

Sunrise at six, heralded by birdsong floating up to the skies

from the lower slopes.

I set

off at seven thirty, when there is bright light all around and the sun has burnt off the

mist and condensation from my windows. The snowy patches over the tops of peaks come

closer and closer; the landscape leaves all greenery behind and covers itself with a

mantle of sulfurous yellow cake. I cross Tichka pass at eight thirty. The last bends

unveil the fantastic ochre Mars-scape of the Anti-Atlas and the utterly bleak and desolate

expanse of desert far below, seemingly drawing a veil over the road I have covered so far

and erasing all memory of life and living.

The Sahara was established as a climatic desert approximately five million

years ago, but it has been subject to short- to medium-term oscillations of drier and more

humid conditions. Even 7000 years ago, there were great grasslands in place of the what we

see today as the grand ergs and dunes of the Sahara. One current geological theory holds

that the change to today’s arid climate was not gradual, but occurred in two episodes

— the first 6,700 to 5,500 years ago and the second 4,000 to 3,600 years ago. Over

these episodes, the Earth’s orbit slipped slightly and the axial tilt changed, from

about 24.14 degrees to the current 23.45 degrees. This resulted in the Northern hemisphere

receiving less sunlight, which, through a complex interlocking set of climactic processes,

‘de-amplified’ the African monsoon. Rivers and streams dried up, sand moved in.

These events devastated the ancient proto-societies of the Algerian and Libyan interior,

now remembered only by rock paintings they left behind. These prehistoric peoples

gradually moved to the Nile Valley where great civilization developed. But perhaps the

Nilotic peoples never really forgot their original range, and the empty expanses kept

calling to those who couldn’t buy into the concept of village and hearth. The Kabyle,

Shawiya, Tuareg and scores of other tribes migrate into the desert during the winter

season when it brings scattered Mediterranean rain, and move back toward the cultivated

land in the dry summer months.

The popular conception of the Sahara as a continent-wide vista of

sand-dunes couldn’t be more wrong. Stretches of dunes – erg -- occupy

only about 15% of the Sahara; most of the rest is a stony desert, consisting of plateaus

of cracked, stony flat rock -- hammada -- or expanses of debri and loosely packed

coarse gravel – reg; so the Sahara is mostly registan. More people

drown out there than die of thirst: when it does rain, flash floods strike without

warning, carrying everything in their path. One can experience diurnal temperature swings

of 50°C (90°F) at this time of the year. Out in the continental interior in Algeria,

winter temperatures drop to -10°C amidst the ergs at dawn; they say the dunes can wear

mantles of frost, and look like great drifts of snow.

Ouarzazate

I coast

down into Ourazazate, stopping on the Sharia ar-Raha right across town near the Glaoua

kasbah of Taourirt.

The air is laden with a soft red dust, gritty, tasting a little

of milk-of-magnesia, so dry that within an hour my lips are chapped and my skin feels like

sandpaper. The wind rises steadily; little whirls and eddies of dust follow me down to the

kasbah.

A minor Berber tribe until the arrival of the French, the Glaoua

shot into prominence mining salt and phosphates in the Anti-Atlas. The chief Si Hammou

Glaoui was made Qaid of Telouet. His son became a trusted aide of the Sultan Moulay

al-Hasan, and got appointed Amir of the High Atlas. The old Sultan died, his sons fought a

war, the Glaoua happened to have backed the winner. Their next chief Al Maidani Glaoui

emerged as Minister of War in the new regime, in charge of fighting the French who were

trying to carve up the Maghreb into colonies. When it became apparent the sultanate in

Morocco was finished, Al Maidani did a deal with the French: in return for keeping the

impregnable High Atlas pacified, he got for his brother the Pashadom of Marrakech and for

his tribe carte blanche over the means of keeping order. By the 1930s, the Glaoua chiefs

had become immensely wealthy, but their end was at hand. They had had to unconditionally

back the colonial office in Rabat as the price of continuing their loot – and the

forces of independence that swept the French out and brought the sultan Mohammed V back in

from exile also put paid to Glaoua hegemony in the South. At the height of Glaoua power,

Taourirt housed dozens of splendid chieftains with hundreds of kinsmen and slaves. Today,

from the outside, the towering ochre houses and ramparts of the kasbah standing shoulder

to shoulder, high-windowed, knot-holed for archers’ arrows testify to the power of

the tribe; but inside, the narrow alleyways are littered with crumbling adobe, the drains

are stagnant and fetid, mangy dogs with opaque eyes limp in and out forlornly through the

doorways.

The Moroccan government has

recently started hyping up Ouarzazate as a vacation destination for European Club Med

types. No doubt they see the place as becoming another Las Vegas sans the gambling and the

liquor, or at least a Santa Fé with its matching adobe buildings. "See Ouarzazate

and Die" proclaims the tourism-department poster (5); but apart from

the Glaoua kasbah, the town is, alas, dull. The wide empty tree lined roads with a helpful

signs every ten meters, the plump bare-armed single French girls sitting by themselves in

the cafés, the empty parking lots at the western-style food-mart, all seem to wear the

expectation of a great coming boom.

Each new place you go to exposes you to vile new bugs that you

have no ancestral immunity against; those of Casa and Marrakech, emboldened by my exposure

to a freezing night in the High Atlas, now proceed to lay me low. My sore limbs and throat

degenerate into a raging headache by the evening. The onset of high fever is deliriously

delicious, akin to getting drunk on some sweet liqueur. I hobble up and down the main drag

of Ouarzazate laying in supplies – slices of cheese-and-olive pizza wrapped in gritty

Arabic newspapers, liquid yogurt, dates and bananas that taste of sand – before

checking into a chhota hotel named Riad Salam and surrendering myself to the fates.

I wake at night drenched with sweat, and open the small window to

the south-east to let in some cool air. It is utterly silent, I am looking out over the

tops of date palms beyond the Oued Drâa, towards the empty barrenness of the Djebel

Sarhro, a shape darker than the darkness all around. Over all this the Sahrawi sky, not

dark like the land but deeply, luminously blue, not even far away, so close you could

reach out and touch it. My head spins with fever, I feel myself being dropped from a very

high altitude somewhere beyond the sky’s dome, floating slowly down like an orb to

the soft embrace of a dune.

Ait Benhaddou

The hotel

has a very pleasant inner courtyard – paved with indigo-and-white tiles, surrounded

by shady trees, around a cool gurgling cistern filled with water. It’s about ten in

the morning, I lie stetched out on a couple of chairs borrowed from the lobby, alternately

dozing and chatting with Suleyman, the jobless kif-smoking doorman. The hotels were

very full last year, when some of the crew of Kundun were here to shoot. Tibet and

the Anti-Atlas are both essentially deserts beyond mountain ranges, though of course the

former is at a much higher altitude. Suleyman tells me how this area used to be a favorite

of the American film companies – I should definitely not miss Ait Benhaddou, where

some of the desert scenes of Lawrence of Arabia, Jesus of Nazareth, Un Thé au Sahara and

The Man Who Would Be King were shot.

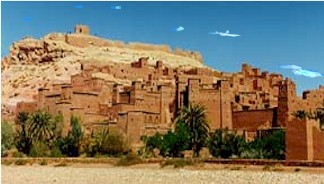

The village of Benhaddou is about 20 miles up the road from

Ouarzazate, on the banks of a precariously surviving nullah. It turns out to have a

gloriously preserved, vaguely extra-terrestrial kasbah. Had most of the inhabitants not

moved to more ordinary settlements on the other side of the river, you could probably

promote Ait Benhaddou as the place where everyone has his own fortress.

It is Friday, and, by the time I drive up, the small population

has gathered in a green field by the channel of the Ounila for the noon prayers. I have

the place to myself, wandering amongst the high terraces and corridors of the upper

levels. The jumble of side-by-side houses intersecting at all sorts of angles look like

they’re made of adobe, but on closer inspection the construction material turns out

to be chips of stone bound by clay into sun-dried bricks – called pisé. Most

individual houses are long, thin towers three or four floors high, the floors made of

wooden beams thatched with palm fronds. Ladders, sometimes built into the pisé,

connect the various levels from the outside and the inside. The lowest level is typically

a pen for sheep and cattle, and the next higher level the kitchen; a hole in the center of

the kitchen floor ensures that scraps can be disposed of easily. Inner balconies surround

the kitchen, leading presumably to bedrooms. The highest level, a loft like space with

rectangular windows, is lined with mats and functions as the living room where the men sit

and talk and drink tea. It is windy when the reed flaps of the windows are opened; looking

out, I can see for miles as the Sahrawi light dances around the little room – past

the fields, past the date trees and the bare hills, far away to the merciless hammada

beyond.

Asabiya

Glaoua and Tuareg; Almoravid and Almohad; Berber

and Arab. Driving back to Ouarzazate from Benhaddou, I reflect upon the tribal substratum

of the Maghreb. More than six hundred years ago, writing in the seclusion of a small

village in modern-day Algeria, a Maghrebi court official named Abd al-Rahman ibn Mohammad

ibn Khaldûn had laid

down the basic philosophy of tribal group dynamics that underly so many societies. This

work revolutionized the science of history and articulated an entirely new discipline of

enquiry called Umraniyat (Sociology). Ibn Khaldûn, forgotten for many years in Europe and lost even to the Arabs, was

rediscovered in the 19th century and translated first to French, and then to

English. Arnold Toynbee called Ibn Khaldûn’s Muqaddimah ‘the greatest work of its kind

that has ever yet been created by any mind in any time or place’.

Ibn Khaldûn was born in Tunis in 1332 into an aristocratic family

which claimed descent from 7th century Yemeni settlers of Spain. His clan

enjoyed great prominence in the courts of al-Andalus, in Africa and in Spain. His

formative years were a time of enormous political upheaval in North Africa -- with the

Hafsids, the Merenids, Banu al-Wad and others fighting over their various satrapies. He

was taught the Quran and Hadith, the philosophies of ibn Rushd and ibn Sina, Arabic poetry

and grammar, as well as the history of the Almoravids and Almohads who were just entering

into legend. He joined government service at twenty, and spent his career working for the

Merenids of Fes, the Sultans of Granada, the Hafsids in Tunis, and the Seljuk Turks in

Cairo. His tasks were largely those of administrator and diplomat: in 1364 he was made

head of a mission to Pedro the Cruel, ruler of Castille, to help ratify a peace treaty

with the Moors; in 1400, he negotiated with Timur and his Tatar hordes during the siege of

Damascus. Wherever he went, Ibn Khaldûn seems to have made enemies, perhaps because of his unwillingness to

suffer fools gladly; embittered by the resultant vicissitudes of political life, he took a

sabbatical around 1376 -- living for three years in a fortress-village near Oran, working

on the monumental Kitab al-‘Ibar, his History of the World. In 1377,

‘with words and ideas pouring into my head like cream into a churn’, he reported

the completion of the Muqaddimah (Prolegomena or Introduction) to this History.

Today, the Muqaddimah is considered to be the earliest attempt

made by any historian to understand the patterns that underlie changes in man’s

political and social organization. "Rational in its approach, analytical in its

method, encyclopedic in detail, it represents an almost complete departure from

traditional historiography, discarding conventional concepts and clichés and seeking,

beyond the mere chronicle of events, and explanation – and hence a philosophy –

of history."(6)

The first thing you notice in reading Ibn Khaldûn is his attempt to

validate historical data critically. "Al-Masudi and many other historians report that

Moses counted the army of the Israelites in the desert. He had all those able to carry

arms, especially those twenty years and older, pass muster. There turned out to be 600,000

or more. In this connection, al-Masudi forgets to take into consideration whether Egypt

and Syria could possibly have held such a number of soldiers. Every realm may have as

large a militia as it can hold and support, but no more ... an army of this size cannot

march or fight as a unit. The whole available territory would be too small for it. If it

were in battle formation, it would extend two, three or more times beyond the field of

vision. How, then, could two such parties fight with each other, or one battle formation

gain the upper hand when one flank does not know what the other flank is doing! ... Also,

there were only three generations between Moses and Israel, according to the best informed

scholars. Moses was the son of Amram, the son of Kohath, the son of Levi, the son of Jacob

who is Israel-Allah. This is Moses’ genealogy in the Torah. The length of time

between Israel and Moses was indicated by al-Masudi when he said: ‘Israel entered

Egypt with his children, the tribes, and their children, when they came to Joseph

numbering seventy souls. The length of their stay in Egypt until they left with Moses for

the desert was two hundred twenty years. During those years, the kings of the Copts, the

Pharaohs, passed them on (as their subjects) one to the other. It is improbable that the

descendants of one man could branch out into such a number within four generations."(7)

Man, Ibn Khaldûn says, cannot live by himself without

co-operation from other men. By himself, a man would need more time than his life-span

allows to make all the things he needs to live. The ability to think and the ability to

speak. God’s gifts to men, enable them to cooperate towards common weal – an

individual accomplishes something from which his fellows profit. Over time, cooperation

between individuals results in a complicated social process called tamaddun –

urbanization. But because men still remain basic animals underneath, social organizations

can exist only when a restraining authority governs over them, dispensing justice,

restraining the aggressive against the meek.

This governing authority, Ibn Khaldûn says, evolves into

umran – society, civilization. Populations in stable societal organizations grow,

and higher forms of civilized behavior result. But since there are different societies,

what causes the differences in the power, behavior and influence of different societies

observed throughout history?

Ibn Khaldûn’s answer is to propose a quality he terms asabiya

– solidarity or group consciousness – from the Arabic root asb, or nerve.

The consciousness that they are part of a group, and the ability to act in concert, driven

as if by central impulse, exists in some groups more than others. The closest asabiya is

seen between those with direct blood ties -- members of a family or clan -- but people

with common descent, as in a tribe, can also share asabiya. In a tribal or group sense,

asabiya is a collective force, a corporated will, giving both striking-power and

staying-power to a group animated by loyalty, a common outlook, or ideal, based on

physical or spiritual kinship. A group with powerful asabiya achieves predominance over

other groups. Thus dynasties and states are founded.

As long as the asabiya remains healthy, the dynasty and state

prosper; cities and populations grow till there is surplus labor that can be channeled

towards the development of refinements and luxuries – sciences, poetry, arts and

crafts. Luxury, however, carries within it the seeds of decay and destruction. The rulers

spend more time in enjoying the luxuries of power than remaining in touch with the men

whose asabiya sustains them; taxes on the many increase to support the indolence of the

few. Gradually, the dynasty loses the reins of power, and some group of outsiders, whose

asabiya is stronger, overthrows the decayed polity and the cycle of dynastic history

starts again (8).

Dynastic glory, ibn Khaldûn observes, typically lasts four

generations. "The builder of a family’s glory knows what it cost him to do the

work, and he keeps the qualities that created his glory and made it last. The son who

comes after him had personal contact with his father and thus learned those things from

him. However, he is inferior to him in this respect, inasmuch as a person who learns

things through study is inferior to a person who knows them from practical application.

The third generation must be content with imitation and, in particular, reliance upon

tradition. This member is inferior to him of the second generation, inasmuch as a person

who relies upon tradition is inferior to a person who exercises independent judgment. The

fourth generation is inferior to the preceding ones in every respect. Its member has lost

the qualities that preserved the edifice of glory. He despises those qualities. He

imagines the edifice was not built through application and effort. He thinks that it was

something due to his people from the very beginning by virtue of their descent, and not

something resulted from group effort and qualities ... he keeps away from those whose

group feeling he shares, thinking that he is better than they. He trusts that they will

obey him because he was brought up to take obedience for granted, and he does not know the

qualities that make obedience necessary – humility in dealing with mean and respect

for their feelings. He considers them despicable, and they in turn despise him and revolt

against him."(9)

Since Ibn Khaldûn’s time, the structures of the traditional

asabiya have been somewhat dismantled by globalization, population growth and

urbanization, but the construct remains important, especially to political Islam. In Syria

and Iraq, power is held by the Ba’ath asabiya, a solidarity group founded on

ethnicity, clan and family. In Algeria, the ruling asabiya annulled the 1992 general

elections when it saw the FIS coming into power through the polls. In Pakistan, both the

PML and the PPP are arms of large families with industrial and land holdings. Indonesia

under Suharto was a narrow asabiya that failed spectacularly, perhaps bringing back

Sukarno’s asabiya in the process. In Afghanistan, a radical fusion of Pushtoon and

Wahhabi asabiyas has battled the Tajik asabiya to the destruction of the country. Iran is

now transitioning into the third generation of the asabiya of Qom that led the Islamic

revolution, and Arabia into the third generation of the asabiya of ibn Saud. In all of

these cases, asabiya has led to the establishment of entrenched vested interests and

clientele networks, more concerned with their own prosperity than with that of the state.

This has been a stark failure of political Islam.

North of the Maghreb, the asabiya of the Franks and the Saxons

perhaps had a hidden streak; when mated with modernity, it produced not only nationalism

but individualism. The notions of the individual and his liberty helped create separate

institutions and associations strong enough to prevent dynastic tyranny, associations

which individuals could enter and leave freely; the institutions and associations of the

West, in a sense, got connected horizontally rather than vertically. Ibn Khaldûn defined

the state as ‘the institution which prevents injustice other than such as it commits

itself.’ The Arabic, Turkic and Persian states functioned only under a strong

monarch’s asabiya. In the West, dynastic command weakened till there was no

over-arching authority; and so people and groups were forced to negotiate with each other.

The tribal groups of Ibn Khaldûn stayed societies based on status or kinship; the Western

ones gradually became societies based on contract (10). Today as in the past, Islamic societies are not good at creating social

structures through horizontal agglomeration – they lack the focus on the individual

to progress beyond the howling asabiya of the vertical group.

Yet a critique of asabiya is not a defense of modern individual

liberty. Does the liberty fostered by Western market economies conflict with the liberty

of personal identity, the liberty of leading a meaningful life? Europe and America perhaps

have more of ‘negative’ liberty -- made famous in the writings of Isaiah Berlin

-- the liberty of not being controlled (though many with an exposure to Western media

would disagree.) This still leaves open the question of ‘positive’ liberty --

the liberty of doing what one wants, the liberty produced by the individual’s

identity. ‘Freedom for what?’ has been the natural question that proponents of

individual freedom have failed to answer. For the existentialists, freedom was in acting

as a pure, distilled essence of human; but, removed from all contingency, such freedom

lost all meaningful context in which it could function.

Be as it may; what happened or not in Paris or Tehran centuries

later perhaps should not be allowed to diminish the import of what Ibn Khaldûn said. If

his failure is in seeing the individual, his contribution is in interpreting history not

only in a political context, but in laying emphasis on the consideration of environmental,

sociological and economic factors governing apparent random events. In addition, his

writings provide clues to the knowledge of al-Andalus; some of which, no matter what the

subsequent trajectories of societal development, took the rest of Europe centuries to

realize and articulate: "The earth has a spherical shape and is enveloped by the

element of water ... one might get the impression that the water is below the earth. This

is not correct. The natural ‘below’ of the earth is the core and the middle of

its sphere, the center to which everything is attracted by gravity. All the side of the

earth beyond that and the water surrounding the earth are ‘above’ [this

core.]" (11)

Weeks later, I was to see the Muqaddimah manuscript lying at the

Qayrawain mosque in Fes. It didn’t seem to be in very good shape. But the Islamic

world has woken up to the importance of Ibn Khaldûn; I was told an agreement has been

signed here between Morocco and the Islamic Development Bank, under which the bank will

give a grant of $260,000 to the rescuing of the 2300 manuscripts at the Main Mosque

Library.

As for the last days of Ibn Khaldûn himself, not much is known,

except that he moved eastwards late in life, was appointed and dismissed from the post of

a judge of the Maliki rite five times -- all because of various quarrels with the rulers

of Egypt, who he considered to be untutored fools. He died in 1406 and is buried in the

Sufi cemetery outside Cairo.

Previous: Marrakech

Next: Western Sahara

|