| Al-Maghreb Al-AqsaThe travel narrative is the most

accommodating of genres – if it is a genre. It can accommodate almost every mode of

style, from the epic to the textbook ... Those who make journeys and write them up can

stuff just about anything they happen to know – history, folklore, literary

criticism, architecture, art, biography, anthropology, natural history, politics, even

gastronomy – into the commodious duffel bag of the travel book; and we, the readers,

usually follow along gullibly, swallowing all this lore, in the childish hope of

eventually finding out where the road goes and what happens along it or beside it.

Larry McMurtry.

Casablanca

It is World

War II in Casablanca. Cynically neutral Rick Blaine, former American and former freedom

fighter, runs a speakeasy in town. With the fall of France, Gestapo Major Heinrich

Strasser arrives in Casablanca, and the sycophantic Vichy police chief Captain Renault

does what he can to please his new master, including detaining Czech underground fighter

Victor Laszlo. The Moroccans in the movie are faceless, the story could have been placed

in Sarajevo without too much editing. Much to Rick's surprise and bitterness, his one time

love Ilsa, who ran away from him in Paris, is now with Laszlo; he agrees to help her

escape with her lover ... Renault is immediately suspicious, and stops by to interrogate

Rick. ‘What are you doing here?’ ‘I came to Casablanca for the

waters.’ ‘What waters? We’re in the middle of a desert!’ ‘I was

misinformed’ ... In the closing scene at Casablanca airport, Rick (Humphrey Bogart)

shoots Strasser (Conrad Veidt) who is calling for help to stop the aircraft in which Ilsa

(Ingrid Bergman) and Laszlo (Paul Heinreid) are about to fly off. A van-load of gendarmes

soon arrives at full pelt, but Renault (Claude Rains), the honneur of France

finally getting the better of him, calmly orders, ‘Major Strasser has been shot.

Round up the usual suspects.’ A classic, a cliché.

Once again, I am waiting at a station in the middle of the night; this

time, it is outside the Mohammed V Airport at Casablanca. The runways in the movie must

have been on a Burbank set, for in reality there is a good hour on board a clanking

carriage between the neon of the terminals and the dim lights of town. Both the bogies

which make up this airport train are dark, and moonlight bathes the gentle contours of

sand hills outside, here some trees, there a tangle of bidonvilles. Apart from me,

there are a couple of chain-smoking young men – airport workers returning home --

stretched out on the seats. None of the other scattered passengers of my near-empty Royal

Air Maroc flight from London seem to have bothered waiting for this last train.

The station, when it finally comes, is dark too. The train stops,

suddenly there are swinging lamps and shouts in the night. In the confusion, I barely have

the time to get off before the clanking train lumbers away. I soon find out this is

Casa-Voyageurs, a satellite station four miles east of town, and that I should have waited

for Casa-Port, where the hotels are.

Outside, in the dimly lit station square, there is still a little

bustle left. As I step out, a large jalopy drives up and a burly man in skullcap and

djellaba pokes his head out. Taxi? I get in, but almost before I have closed the door, a

smaller black-and-yellow cab races across the station square and rams into the door,

almost taking my arm off in the process. The two drivers leap out. It seems that the one I

was about to patronize was a moonlighter, and not a proper taxi, and that the other cab

had waited in the ranks for hours for a fare ... Leaving them to their altercation, I walk

away and get into a minibus to Port.

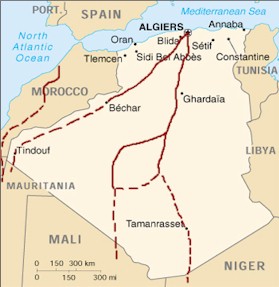

I am in Morocco to see, and perhaps cross, the Western Sahara. Throughout

history, there have been but a handful of land routes connecting the Mediterranean coast

to western Africa. In the east, there is the Route du Hoggar, which runs almost straight

south from Algiers, passing between the two Grand Ergs, turning towards the Hoggar

Mountains and Tamanrasset beyond them them, leading into Niger. The next crossing –

historically the Route du Tenezdrouft -- is 500 kms to the west: via Reggane and Borj

Mukhtar into Mali. Another 1000 kms and you have the Route du Mauritanie connecting Beni

Ounif to Tindouf and leading to Mauritania. These routes are hardscrabble at the best of

times – long unpaved stretches, lack of water, sandstorms and alleged Tuareg

banditry; with the political turmoil in Algeria and gruesome media reports of violence

against foreigners, they prove to be easy to postpone for future trips. That leaves the

Coastal Route, from Marrakech over the Atlas towards Ouarzazate, skirting the western

flank of the desert, along Dakhla into Noahdhibou and then south to Senegal. This is a

fine route that can be followed to see some desert scenery and perhaps technically claim a

Sahara crossing; the only small matter is that of land mines.

In 1974, Spain decided to abandon its Western Sahara territory consisting

of the provinces of Saguia al-Hamra and Rio de Oro, partitioning it between Morocco and

Mauritania. With active encouragement from king Hassan II, 350000 Moroccan civilians

walked in as part of the notorious Green March into Sahara. In 1979, Morocco annexed the

Mauritanian part of the Western Sahara. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia

Al-Hamra and Rio de Oro (Polisario), claiming to represent the desires of the indigenous

tribes for independence, had been getting radicalized under the lingering Spanish rule.

Training its sights on the Moroccans as the ‘new colonizers’, the Polisario ran

a guerrilla warfare of sorts for more than a decade, mining all roads into Western Sahara,

until their backers Algeria and Libya lost interest and reached separate ententes

with Rabat. The UN stepped in with a cease-fire that has held for most of the 90s, but it

is still difficult to cross from Morocco into Western Sahara and Mauritania. Moroccans

issue travel permits in Dakhla, and once a month the army escorts civilian convoys across

the minefields to Noahdhibou. My plan is to drive down the Sahara-facing slope of the

Atlas (the anti-Atlas), and then hook up with one of these convoys at Dakhla. With

relations between Morocco and Mauritania still not-quite convivial, you can apparently

only go within a couple of miles of the border with the Moroccan Army;

then, you have to cross over some sort of no-man’s land to the Mauritanian side, and

seek the help of the

authorities there to guide you across the rest of the minefields.

The garden-variety anti-personnel mines that are littered in

parts of the south-western Sahara will blow off your legs and could kill you if you step

on one, but are fairly safe to drive over: you could get away with no more than a ruined

tire. There are some meaner, larger, anti-vehicle mines. I read a 1970s account of someone

driving his Unimog over a powerful mine near Nouadhibou. The heavy vehicle was completely

destroyed, but the occupants lived. Apparently, every year, a few Sahara travelers set off

mines; while the easiest way to avoid setting off a mine is to avoid known minefields

altogether, the next best is to hire someone as guide, in my case the Moroccan Army.

Where are the mines? Starting from the west, the lateral border

between Morocco and Mauritania is mined, though by now everyone knows the risks of leaving

the piste or mis-calibrating the GPS when crossing south. The first Mauritanian

checkpoint, they say, has a mass of tracks and there are no warning signs -- in 1998 a

Land Rover apparently hit a mine just a couple of meters from existing vehicle tracks with

one fatality. There are certainly mines alongside the Laayoune - Bir Mogrein road leading

to the northwestern corner of Mauritania; a truck from the Paris-Dakar rally caught one a

couple of years ago. Elsewhere in Mauritania, areas east and south of Ouadane are also

said to be mined; there are said to be mines north of the crater near the El Beyyid well

and rock paintings. There are also mines between Algeria and Morocco in the Hammada du

Drâa region between Tindouf and Bechar, though no regular trails cross this area, to

protect access to the Polisario refugee camps in the Hammada. Mali is thought to be

mine-free, as is Algeria. In Niger, it was reported in 1997 that Tuareg rebels were laying

mines in the Djado Kaouar region.

I step

out in the crisp winter Casablanca morning, the roads not yet loud with carts and petit-taxis.

I’m on my way to see the Hassan II mosque. In 1195, the Almohad sultan Yakub

Al-Mansur embarked on building the largest minaret in the world. It was intended to be 60

metres high and 20 metres wide at the base, but was abandoned after the Sultan’s

death, having reached some two-thirds its intended size. This is called La Tour Hassan,

and it still stands in Rabat, a crumbling testimony to a long-dead Moor’s grand

plans. Eight centuries later, the present king Hassan II (1) commissioned another project to build a grand minaret.

Construction was started in 1987 and completed in 1993, at the cost of nearly a billion

dollars. It is a people’s monument – a special ‘mosque tax’ was levied

on all Moroccans to finance the project – and can hold 100,000 worshippers during namaaz.

The roof of the central hall can swing open, to reveal the heavens to the assembly. The

minaret, at 200-plus meters, is the tallest in the world; at night, a green laser light

points out the direction to Mecca. There is some magnificent Gueliz tile-work on the walls

of the mosque in a huge non-repeating pattern, but other than that the effect is somewhat

akin to a Walt Disney movie set of the Arabian Nights. The mosque occupies a large acreage

right on the water’s edge along the Atlantic, but there is not a single tree on the

grounds – the entire plot has been overlaid with beige stone, and looks like a

giant hotel lobby, not a blade of grass peeks out. As the sun climbs, I wander

around on this rapidly heating floor, the sun glittering off the polished tiles, and think

of the understated majesty of the Mughal domes in India, at peace with themselves in their

cool gardens.

Berbers & Moors

Later in

the day, I go to the rental agency at Place des Nations Unies to collect the Mitsubishi

4x4 that will bear me south. It is possible to cross the Sahara without 4-wheel drive, but

once you come into the sand, it is better to have one. A good 4x4 is able to pull one

through most cases without one having to resort to digging; in most cases, if you get

stuck, you can drag yourself out, centimeter by centimeter, with the low 4x4 gear. For

dealing with harder situations, the vehicle comes with a winch, which can be used with an

anchor buried in the sand to help in extraction. Finally, if all else fails, there are

sand ladders and spades -- you dig into the sand and place sand ladders under the wheels

of your vehicle to get a hard surface to drive on.

The streets are full, and while the agency downs its shutters for

namaaz I stand and watch a river of people flow by.

If India can be thought of as having an Aryan north and Dravidian

south, the simple way to think of ethnicity in Morocco is in terms of an Arab north and

Berber south.

In prehistory (around 15000 BC), a mysterious tribe of Neolithic

people appeared in the Capsa (Qafsah) region of Tunisia. The indigenous inhabitants of the

southern Mediterranean coast intermingled with the invaders in a process that brought

Neolithic ways of life to North Africa. The Berbers of Morocco are the descendants of this

Capsian culture.

For 14000 years, they slowly developed a nomadic, pastoral

culture with distinct tribes, migration patterns, languages -- gradually expanding

southwards and pushing the Negroid peoples to sub-Sahara.

As Carthage, Greece, Rome and Byzantium rose in the northern and

eastern Mediterranean, the Berbers were successively colonized or became tributaries of

the dominant culture. In 622 A.D., a Qurayshi trader claiming receipt of divine revelation

in distant Arabia fled from Mecca to Medina to protect his flock from the wrath of

‘idolaters’ -- Islam was born. By 640, the green pennant flew over Egypt; by

669, over Tunisia; by 710, the armies of the Arab Musa bin Nusayr had allied with,

converted or defeated all the Berber peoples of Morocco. While all the Berbers had been

converted to Sunni Islam by the 11th century, and though there were legions of

Berber troops in the Arab forces, the tribes of the Moroccan interior resisted Arab rule

whenever possible; and, at various times, were able to maintain autonomous states, the

most recent of which was established in the Rif region under French Colonial rule. So the

north was gradually filled with Arabized Berbers who adopted the language, dress and

culture of Arabia. The south – especially the mountainous regions of the Rif, Middle

Atlas, High Atlas and Anti Atlas regions – became a stronghold of those who resisted

Arabization.

Moroccan Berbers are divided into several tribes, which speak one

of three principle dialects of the Berber language -- Rifi of the Rif; Tamazight of the

Middle Atlas, the central High Atlas and the Sahara; and Tashilhit of the High Atlas and

the Anti Atlas. In Algeria there is one main Berber dialect, called Amazigh. Out in the

Sahara, a Berber language called Zénète is used. The sole remaining Berber language in

Tunisia, called Chelha, is dying out in our times. These dialects all belong to the

Hamito-Semitic family; the script is vaguely Punic. The Berbers call themselves the

Imazighen – "men of noble origin." There are about 10 million Berber

speakers (one third of the population) in Morocco.

While there are similarities between all the Berber groups, particular

lifestyles vary according to region. The basic Berber economy rests on a fine balance

between farming and breeding cattle. Every tribe depends heavily on domestic animals for

carrying heavy loads, milk and dairy products, meat, and hides or wool. Similarly, every

tribe also relies on seasonal agriculture for survival. Around populated areas, they bring

craftwork to markets. Weaving and pottery are the mainly done by women, whereas men

specialize in woodworking, metalworking, and, surprisingly, needlework

Ibn Khaldûn narrates how the Berbers got their name in his

monumental Kitab al-‘Ibar (Book of History). Ifriqus bin Qays bin Sayfi, of the royal

line of the Tubba`s of Yemen who ruled around the time of Moses, raided the province of

Ifriqiyya (the Arabic Africa was limited to modern Tunisia and Libya; south of

‘Misr’, provinces had their own names, such as Nubia, and were not considered

part of Ifriqiyya), and caused a great slaughter amongst the nomads. When he heard them

speak, he asked derisively what that barbarah noise was all about, and gave them

the name Barbar, which has remained with them since. Carthaginians list three indigenous

peoples – the Libyans, the Numidians and the Mauri, collectively called Barbarii --

around them. The term Mauri is also used by the Romans for the inhabitants of the

Roman province of Mauretania (western Algeria and northeastern Morocco.) The Roman

Mauretania is, of course, different from today’s Islamic Republic of Mauritania,

though the inhabitants of the latter are sometimes called maure (Moor) in French.

So the name ‘Mauri’ gave rise to the word Moor – and this

became a generic term used in Europe from the middle ages to describe not only Arab and

Berber in the Maghreb, but also Muslim and African in general. Shakespeare’s Othello

is negroid; while he is a great general and fearless fighter, he is also

‘thick-lipped’ and simple minded:

- Iago: The Moor is of a free and open nature,

- That thinks

men honest that but seem to be so,

- And

will as tenderly be led by the nose

- As

asses are.

In Shakespeare's time, the Moors had largely been driven out or

executed by the Inquisition. Since the Spanish were the demonized by the Elizabethans (the

Spanish Armada sailed in 1588), the Moors were seen to be earlier victims of a common

enemy – Shakespeare’s treatment of Othello as a sort of fish out of his racial

water is typical of nostalgic regret admixed with sentimental stereotyping with which

Elizabethan society regarded the Moors.

While

Berber groups such as the Kabyles, Shawiya, Tuareg, are nominally Muslim, their observance

of Islamic law is generally lax. Interestingly, the concept of baraka, or holiness,

is highly developed amongst the Berbers. The Berbers believe that many people are endowed

with baraka, of which the holiest are the Sharifs, the direct descendants of

Mohammed. The marabouts form another class of holy men. Among some Berbers, the

Tuaregs in particular, the marabouts are considered to be different from ordinary

men -they are believed to possess the powers of protection and healing, even after death,

and their shrines are carefully tended. It is also interesting, in view of the general

acceptance of Islam, that almost all Berbers -- especially the Tuareg, prefer monogamous

marriages.

In most of the Maghreb, Berber

identity is considered to be a negative, largely because the pastoral Berber societies are

less developed than what is seen in the cities. Almost all city-dwellers see themselves as

Arabs -- Marrakech remains the only city with any Berber identity.

|